By Todd Pengelly

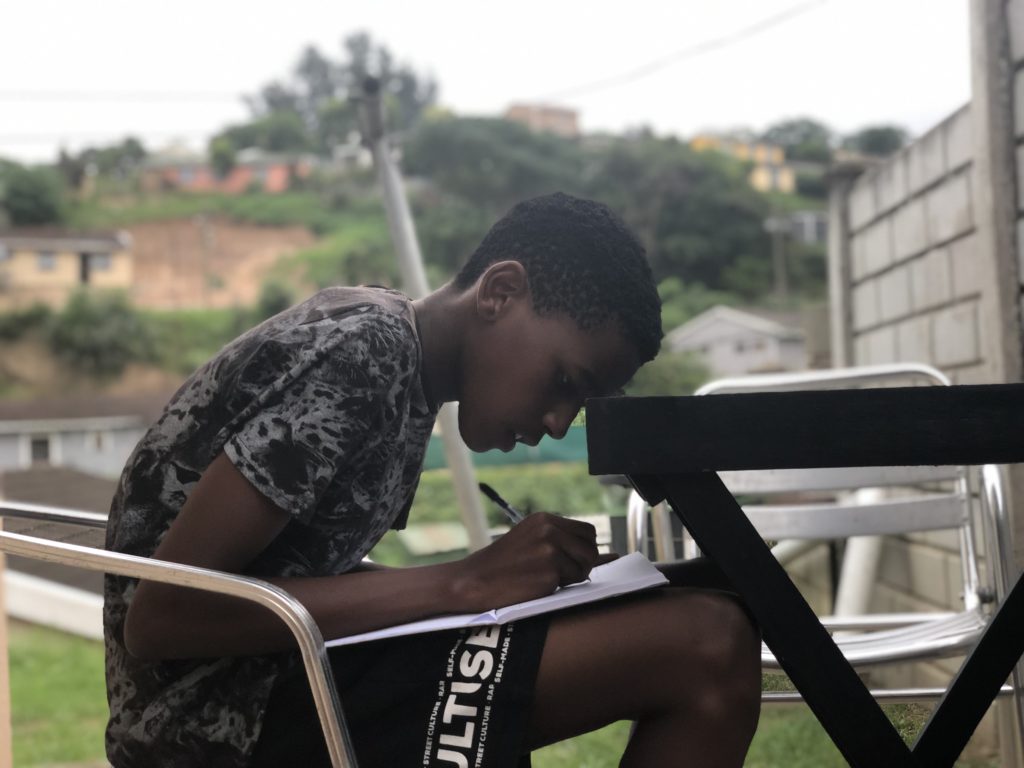

Though his birthday isn’t until May, Thabang, 14, is quick to add the extra year to his age. “I’m 15,” he says when asked his age. “But maybe I’m the kid that’s 200 years old. You know, science says the first 200 year old has probably been born.” It’s an interesting idea, especially coming from a teenager as mature as Thabang is at 14. As Thabang, English name – Kevin, sat sketching in my notebook, I asked him if he was afraid of dying. “Of course I am!” he exclaimed.

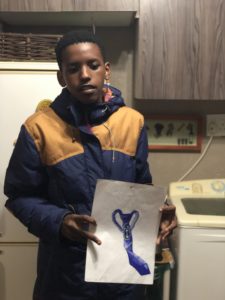

Thabang, who can be found drawing at nearly all times of the day, wants to be an architect when he grows up, although he doesn’t seem too keen on actually growing up. Before realizing his dream in high school, Thabang says he wanted to be a pilot. “But then I went to a jetlab and realised flying was too risky. I can’t do that.” So, he turned away from his risky, high-flying dreams and took up the arts instead. Even though he’d been drawing since he was 8, it wasn’t until high school that Thabang really decided illustration was what he wanted to pursue. “High school changes everything.”

“Everything?” I ask.

“Everything,” he answers.

And while “everything” has changed for Thabang and his personal and academic interests, he is still extremely self-conscious about his work. “I’m not that good,” he points out to me repeatedly. “My friend, he’s good. Your big brother, Siya, oh man – he’s really good. Me, I’m not that good.” It’s not exactly humility. It’s more akin to insecurity. When I pressed him on why he continued to draw if he didn’t think he was good, he responded by saying, “I do art for the sake of art.”

As I sit and watch Thabang’s passion for illustration, a quote from Kurt Vonnegut works its way forward in my memory. “The arts are not a way to make a living. They are a very human way of making life more bearable.”

And seeing Thabang sit with his work, drawing to stay in the moment and not grow old, breathes a new life into the quote swirling in my head. I find out later though, that there is another part to this quote, a part I had forgotten or never known. As if responding to Thabang’s insecurity of his art, Kurt Vonnegut continues, “Practicing an art, no matter how well or badly, is a way to make your soul grow, for Heaven’s sake.”

So, that’s what Thabang does. He sits, and he draws, and he grows, whether he wants to or not.