Cato Manor can be chaotic. Houses undulate on uneven ground with rainbows of laundry drying on the line. On weekdays, dogs bark the neighborhood to sleep. On weekends, electronic music reverberates to the beat of flashing lights and honking minibus taxis filled with people. I’ve never seen them with open seats.

Last year, a man in the community died tragically. His family slaughters a cow and rents a tent to celebrate the anniversary.

My host sister sings all the time. Cooking hot dogs for breakfast, mopping the floor, fidgeting on her phone, there’s Sisi singing Christian gospel.

Inside the family home, there are no closed doors. They’re seen as rude, against the Zulu tradition of an honest and transparent way of life, I am told. There’s no hiding here—especially from my Zulu mama.

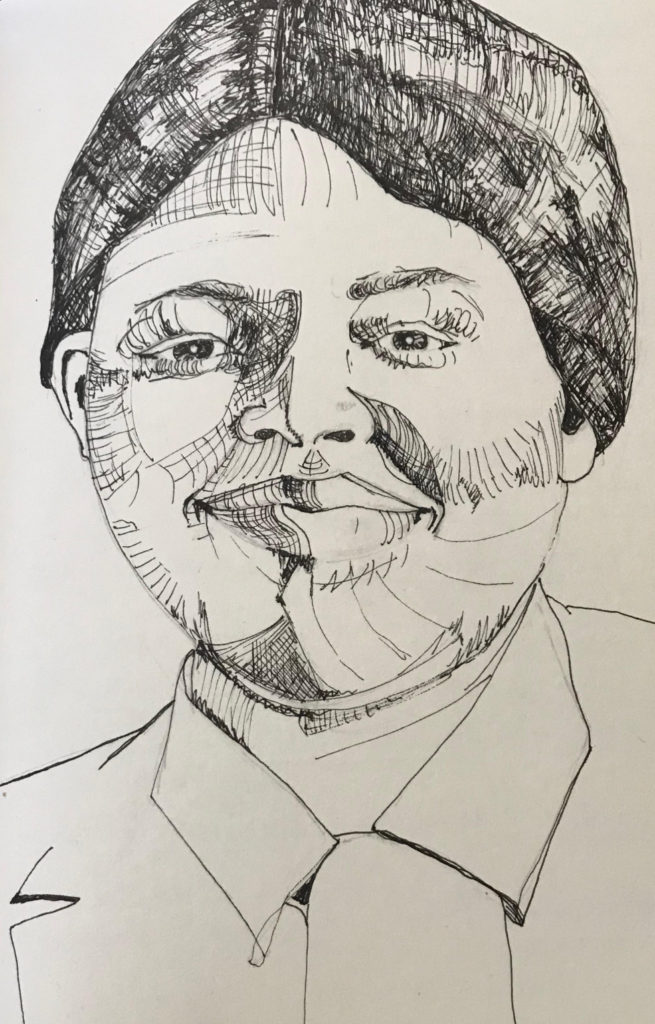

Most of the time she sits on the sofa engrossed in South African soapies. She prefers to speak isiZulu so she barely speaks to me. She’s not afraid to show her frustration when I don’t finish dinner, come home late, forget to unplug the toaster. Electricity is something to save. However, I see her smile for the first time when I show her a portrait I have drawn. Then she commands, “Draw me.” After a week living on Deeside Drive, this brutal honesty isn’t offensive anymore—it’s genuine.

In Cato Manor, I can go for a run down the street and return having made five new friends. I join a soccer game on the street. A neighbour comes out to complement my sneakers.

One night there is a birthday party—a massive barbeque event. Cow (inkomo), chicken, and sausage are grilled over flaming coals until well-done and, well, burnt. I take a bite of the sausage. Coriander and clove explode on my palate. Wait, I wonder, could that be nutmeg?

I say it’s the most delicious thing I’ve eaten in South Africa so far. “That’s the only thing us black people love about Afrikaaners,” a guest says in reference to the boerewors.

Despite moments of feeling welcome, Cato Manor is not my home, however much I try to make it so. A man at a coffee shop warns me, “It isn’t safe there. Bad things happen.” One Uber driver dumps me out of the car before we reach my stop in fear of getting shot. My friend gets drugged at a combination car wash-club and we swerve through late-night traffic to save her life. Locals show their kindness in concern, coming to the silly foreigners’ aid.

This place is somewhere in between feeling safe and scared every day.