By Renny Simone

MAIN PHOTO: A swarm of desert locusts, taken in 2014 near Satrokala, Madagascar (lwoelbern from Wikimedia Commons)

Nearly a month before sub-Saharan Africa recorded its first coronavirus infection, Somalia declared a national emergency in response to a different natural threat: swarms of desert locusts.

Somalia’s Ministry of Agriculture called the insects “a major threat to Somalia’s fragile food security situation” in a statement reported by the BBC in early February.

Two months later, as governments worldwide focus attention and resources on fighting the coronavirus pandemic, the locust plague has taken a turn for the worse.

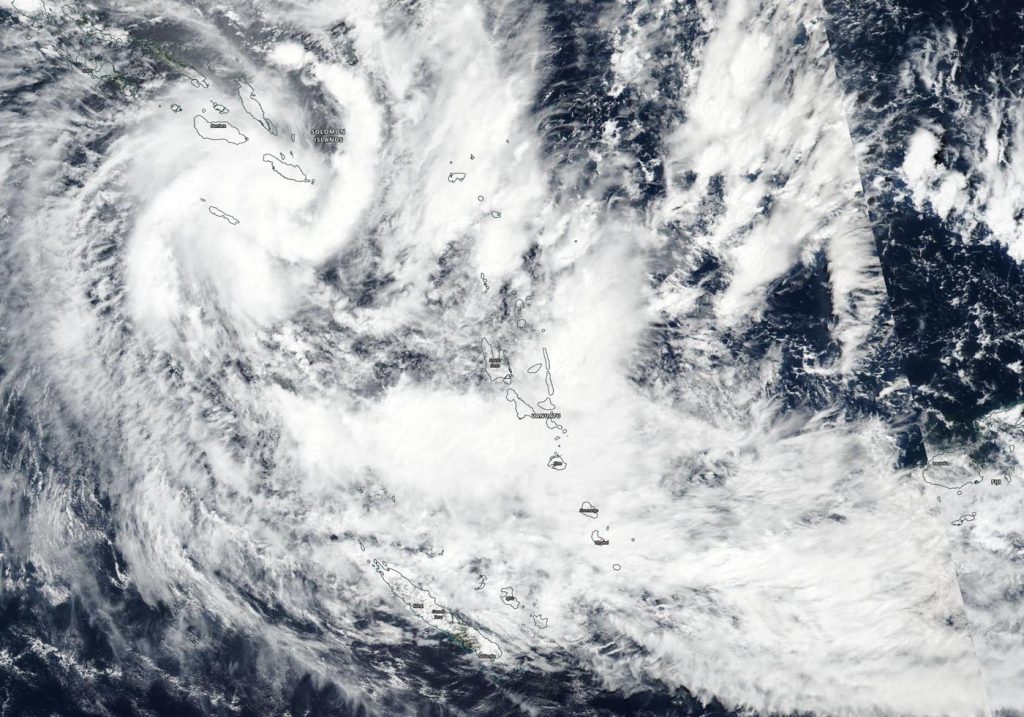

The Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) has warned in its latest report that widespread rains that fell in late March could allow a dramatic increase in locust numbers in East Africa, eastern Yemen and southern Iran in the coming months.

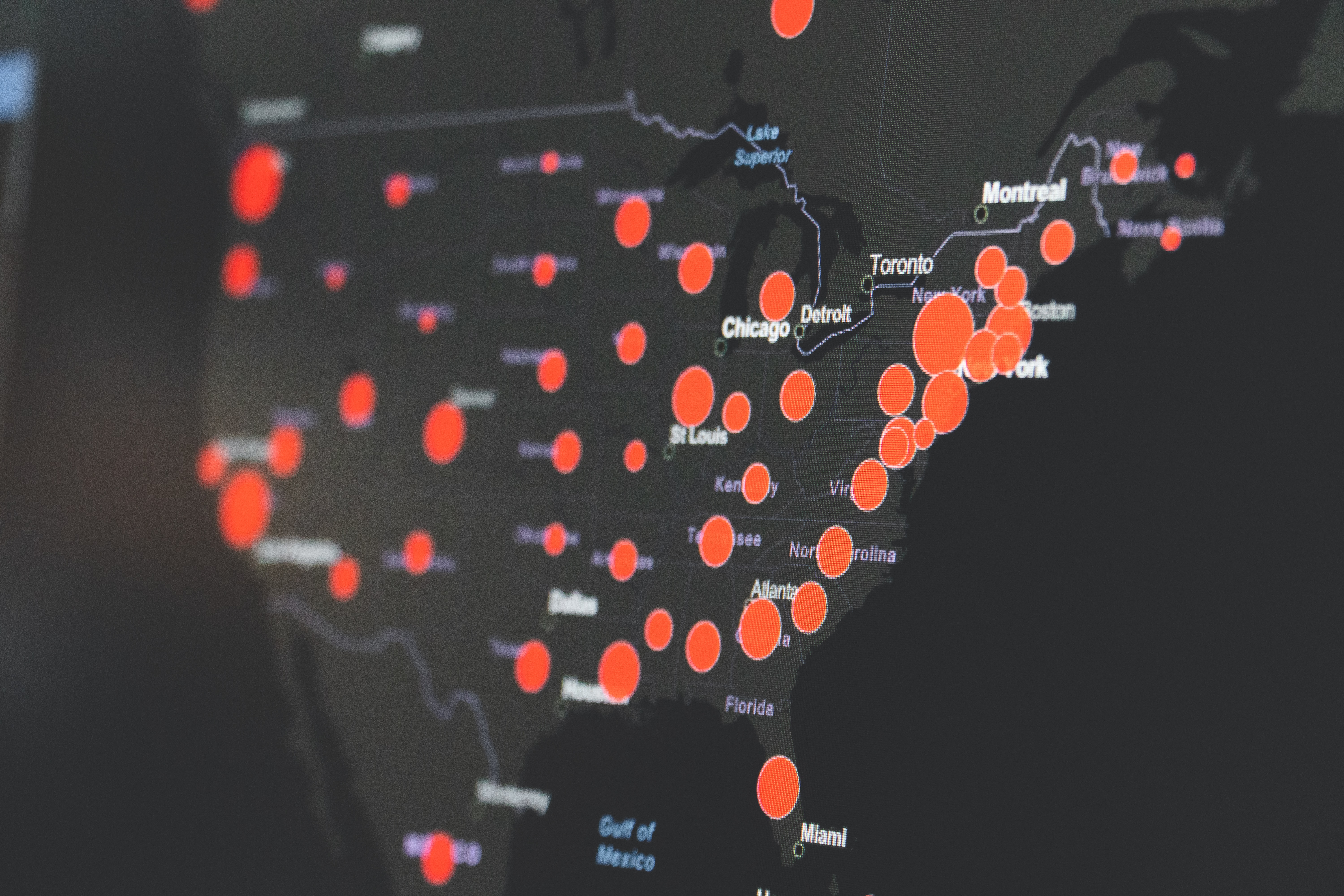

The locust swarms, which feed on crops, represent “an unprecedented threat to food security and livelihoods” in affected nations, it said. Somalia, Kenya, and Ethiopia have been the hardest hit, but other East African nations, as well as parts of the Arabian Peninsula and Southwest Asia, are also at risk.

The African Development Bank recently approved $1.5 million in emergency funding to help control the infestations. A total of nearly $150 million will be required to stem the spread, and there is a significant shortfall, according to a statement released by the African Development Bank Group.

Coronavirus presents additional challenges. International attention has been monopolised by the pandemic, and funding is in short supply. More pressingly, flight restrictions have prevented the delivery of pesticides to affected countries. Some, including Kenya, are rapidly running out of reserve stocks.

“If we fail in the current [regional] control operations, because of lack of pesticides, then we could see four million more people struggle to feed their families,” said Cyril Ferrand, FAO’s head of resilience for Eastern Africa.

“If we don’t have pesticides, our planes cannot fly and people cannot spray and if we are not able to control these swarms, we will have big damage to crops,” Ferrand told Reuters.

The pesticide deficit is another symptom of coronavirus-related travel restrictions, which pose the greatest threat to countries dependent on the delivery of international aid. Some organisations are in the process of negotiating “humanitarian corridors” to make sure necessary aid can be delivered. But in the meantime, Al Jazeera has reported that more than 20 low- and middle-income countries are facing vaccine shortages due to travel restrictions.

Aid organisations are sounding the alarm.

“While the threat posed by COVID-19 must not be underestimated, if the chaos caused by this pandemic is allowed to curtail ongoing humanitarian assistance, the results will be catastrophic,” Doctors Without Borders warned.