By Renny Simone

MAIN PHOTO: A young child and an adult read a storybook together. SOURCE: Lina Kivaka from Pexels

If you want to nurture the little scientist in your child, give him or her a book. That, at any rate, is what the scientists are saying.

A new study published this week has found that children prefer storybooks that tell them something about how things happen – which may help parents understand why their children’s favourite question is, Why?

Jean Piaget, a 20th century pioneer of developmental psychology, often called children “little scientists” because of their natural curiosity and insistence on explanation.

Piaget and others established that children tend to prefer “causally rich” information – that is, information that helps explain “the why and how of the world”.

But the new study by researchers from Vanderbilt University and the University of Texas, published in Frontiers in Psychology, has taken a novel approach to the question.

Where most previous studies have taken place in artificial laboratory settings, the authors of the latest research wanted to see whether the findings could be repeated in a more practical context.

“There has been a lot of research on children’s interest in causality, but these studies almost always take place in a research lab using highly contrived procedures and activities,” according to one of the researchers, Margaret Shavlik, of Vanderbilt University.

“We wanted to explore how this early interest in causal information might affect everyday activities with young children – such as joint book reading.”

Shavlik and her co-authors – Amy E Booth, also from Vanderbilt, and Jessie Raye Bauer from the University of Texas – anticipated that young children would prefer books with more explanatory information to those with less. The researchers selected two books by the same author – one “causally rich”, the other “minimally causal” – and controlled for factors like subject matter, art style, and words per page, minimizing the chance that preferences would be influenced by anything other than causal content.

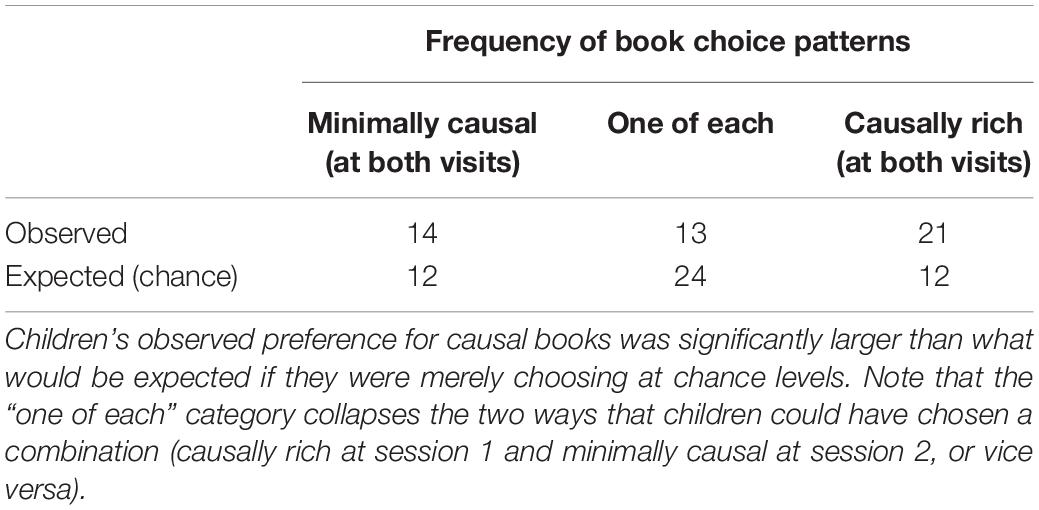

A group of 48 children, all three or four years old, were selected for the study. A female experimenter read both books to each child. Afterwards, the children answered some basic comprehension questions, and told researchers which book they liked better. Two weeks later, the process was repeated, except that the books were read in reverse order.

The results? Over 40% of the children preferred the causally rich book in both sessions. If left to pure chance, only 25% of the children would go for causality both times – leading researchers to conclude that their hypothesis has some validity.

“We believe this result may be due to children’s natural desire to learn about how the world works,” Shavlik said.

SOURCE: “Children’s Preference for Causal Information in Storybooks”, Frontiers in Psychology, Shavlik, Bauer, and Booth

In addition to affirming the causality hypothesis, the study has important implications for childhood literacy. Parents might have better luck getting their child excited about reading if they choose books that explain something.

“If children do indeed prefer storybooks with causal explanations, adults might seek out more causally rich books to read with children – which might in turn increase the child’s motivation to read”, Shavlik said. In other words, adults can stimulate young minds (and make their own lives easier) by picking books that satisfy children’s natural curiosity.

The researchers say these findings raise important questions about the practical relevance of causality. Does causal richness have an impact on how easily kids acquire information? Can these results be repeated in a more natural setting, such as by recording parents and children in their home?

The authors don’t have answers yet, but they believe their study “lays a solid groundwork” for exploring the questions.