By Kimberly Wipfler

MAIN IMAGE: Trash waiting to be sorted at a recycling centre in Cape Town. Source: Kimberly Wipfler

If you’ve opted for a “green” alternative to a plastic product in an effort to help the environment – such as a paper straw or biodegradable coffee cup – you may have been duped.

Environmentalists are increasingly concerned that manufacturers who are offering replacement products may in fact be making the global plastics crisis more difficult to solve. And, they argue, many of the strongest selling points of these products are just not true. In some cases, the “better” product you’ve selected may even be more damaging than the original.

Anti-plastics activist Karoline Hanks calls it classic greenwashing. “They’re making money off people’s good intentions. It’s brutally dishonest.”

Hanks runs numerous campaigns to try to change the way people make consumption choices. The straw debate is one she has personally tested.

The move to alternative straws has gathered momentum since a 2015 video of a sea turtle with a plastic straw lodged in its nose went viral (link) and in the wake of growing awareness of the damage single-use plastics cause to marine life.

The public outcry over their impact has pushed restaurants to move away from providing them. Many now serve alternatives, like paper straws, or have stopped handing them out altogether. But customer dissatisfaction with paper straws, which quickly become soggy, has been a challenge for the food industry.

New options have come into the picture: straws made from “biodegradable” or “compostable” plastics. Patrons can feel good about their green straw choice without risking the inevitable crumbling of a paper one.

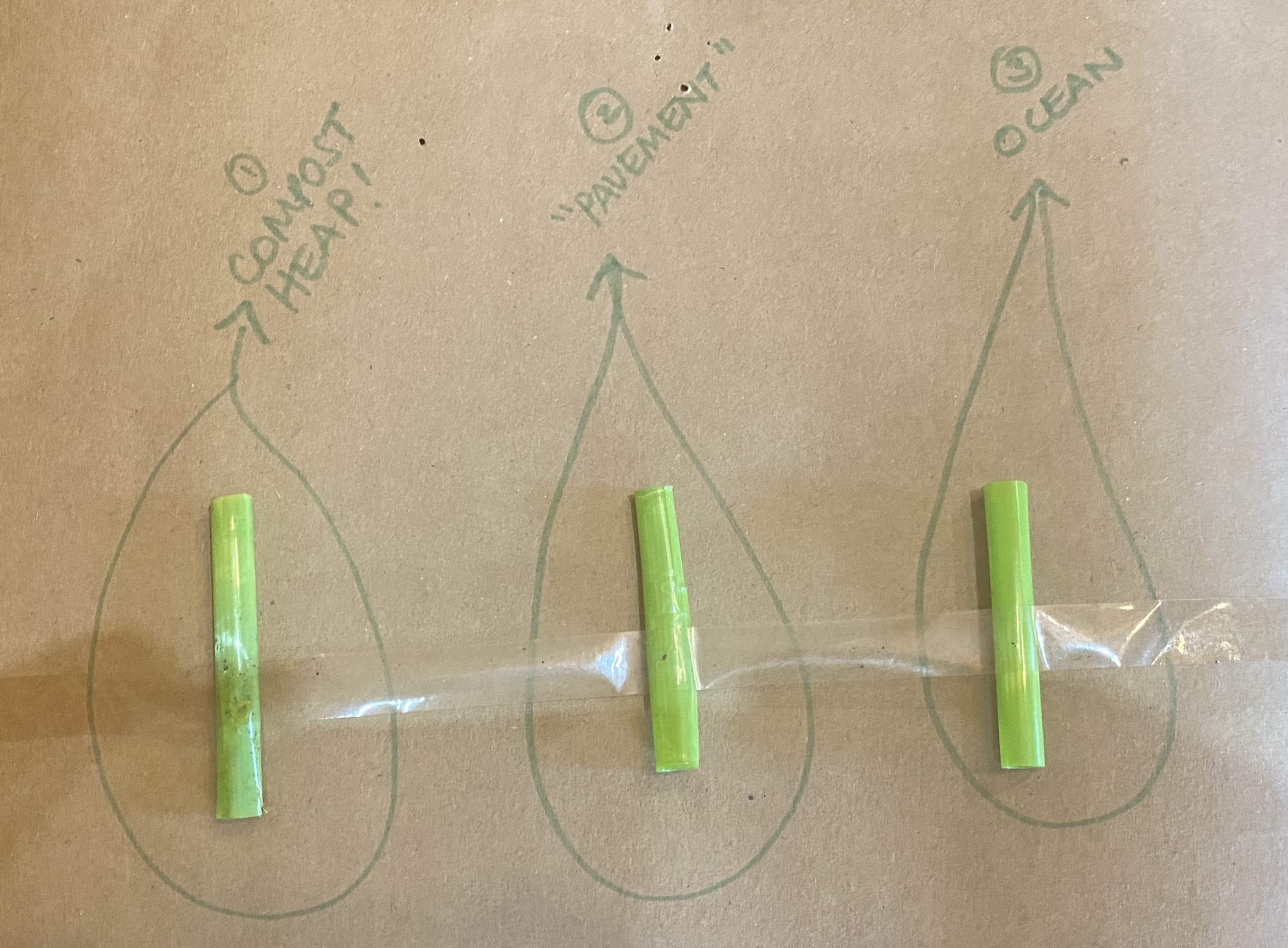

Hanks was served a compostable straw at a restaurant this year and decided to test it’s claim. After three months, sections of the straw kept in three different environments – in her compost heap; in a jar of seawater; and in the open air – showed no visible difference, and no signs of fragmenting.

“In that time, think of the damage that’s been caused. In those three months, these things have choked something, gone up someone’s nose, or become microplastics. Don’t give me this biodegradable bollocks,” Hanks said.

Her home test is backed up by research conducted by UK scientists at the University of Plymouth who found that after three years, so-called biodegradable plastic bags that had been buried in soil or left in seawater were still able to carry shopping without breaking.

Many other products are now promoted for their compostability – from coffee cups to cling wrap and shopping bags.

Plastics SA, which represents a range of players in the industry including polymer producers and importers, converters, machine suppliers, fabricators and recyclers, argues that the misconception that biodegradable plastics will decompose and disappear when left in the environment makes people more complacent. The danger of this thinking, they say on their website, is that research shows consumers are more likely to litter when they believe their waste will decompose. Not all “biodegradable” plastics will do this.

So-called “compostable” plastics pose a similar challenge. Although these items are manufactured to stricter standards – they’re technically required to decompose under industrial composting conditions within three months – it is not immediately clear to consumers that this requires particular conditions which are controlled for factors like temperature, humidity, and aeration.

Compostable and biodegradable plastics need professional processing and will not disintegrate in a normal domestic setting, or in a landfill.

The difficulty with these products has a ripple effect in the waste chain.

In South Africa a key role in this is played by waste pickers who rely on collecting recyclable materials for a living. They collect bags of cans, plastic, cardboard, paper and other saleable materials from refuse bins and landfills, frequently having to travel several kilometres to sell them to formal and informal buy-back centers.

Nompumelelo Njana, a waste picker from Khayelitsha, has been collecting recyclable items from trash bins since 2007. A kilogram of cans, she said, will sell for R8.

Njana works as a coordinator for the South African Waste Pickers Association which is trying to have the law changed, and is hoping to negotiate a more formal role for waste pickers in the waste cycle.

According to WWF, waste-pickers are responsible for collecting 20% of recyclable materials in South Africa, and they account for as much as 80% of recyclable PET bottles. The South African Plastics Recycling Organisation (SAPRO) website says waste pickers saved government R748.8 million in 2014 through their informal recycling services, yet waste picking remains an illegal activity.

Despite it being against the law, there are buyback centres in most cities in South Africa. On the outskirts of Stellenbosch 200 to 300 waste pickers turn up every day with materials to sell. It’s a precarious existence. The price of recyclables can fluctuate dramatically, depending on supply and demand, and what might be desirable today may have no value tomorrow if there’s no market for them.

The arrival of “biodegradable” plastics has made the job of waste pickers and recycling plant owners even more difficult.

Johan Conradie, director of recycling plant Myplas, said because the plastic alternatives look just like regular plastic, waste pickers may gather these items and be unable to sell them. But more importantly for consumers down the line, these products can contaminate recycling processes and pose a threat to the durability of the new, recycled items they become.

This would not only jeopardise the quality of the product it would also jeopardise adherence to international standards. Currently, Myplas is one of two recycling plants in SA that meets ISO 14001, the international environmental management standard.

Conradie, who also serves as chairman of SAPRO, said it would be better to ensure that recycled plastics are made from quality materials than to promise various degrees of degradability that are poorly understood. If quality plastics were used in the recycling industry, products would stay within the economy for longer instead of heading to landfill.

“In the end, circularity is the more long-term, sustainable solution,” he said.

“You’re never going to be able to feed 8 billion people without plastic. You would literally not be able to sustain the earth. The question isn’t, ‘Is there a place for plastics?’ It’s, ‘What do we do with the plastics when we’re done?’, and that’s the tricky bit.”

A WWF media release argues that a raft of limiting factors in the recycling industry means that a lot of material that technically could be recycled goes to landfill or ends up in the environment. These factors include a lack of infrastructure and poor collections systems, market conditions, a lack of equipment and budgetary constraints as well as over-engineered materials.

Another issue is the way packaging is labelled. According to Zaynab Sadan, a project officer for the Circular Plastics Economy Programme at WWF, unclear labelling means that non-recycling materials get sent to waste management facilities. At some, such as at the Kraaifontein Integrated Waste Management Facility, these are hand sorted into recyclables such as paper, tins, plastic bags and cardboard and the rest is sent to landfill.

Janvier Rusasa, assistant plant manager at Kraaifontein said that the plant receives waste from almost 30 000 households and processes about 1 000 tons of waste each day.

About 20% of the waste it receives is plastics, and at least 12% goes to landfill.

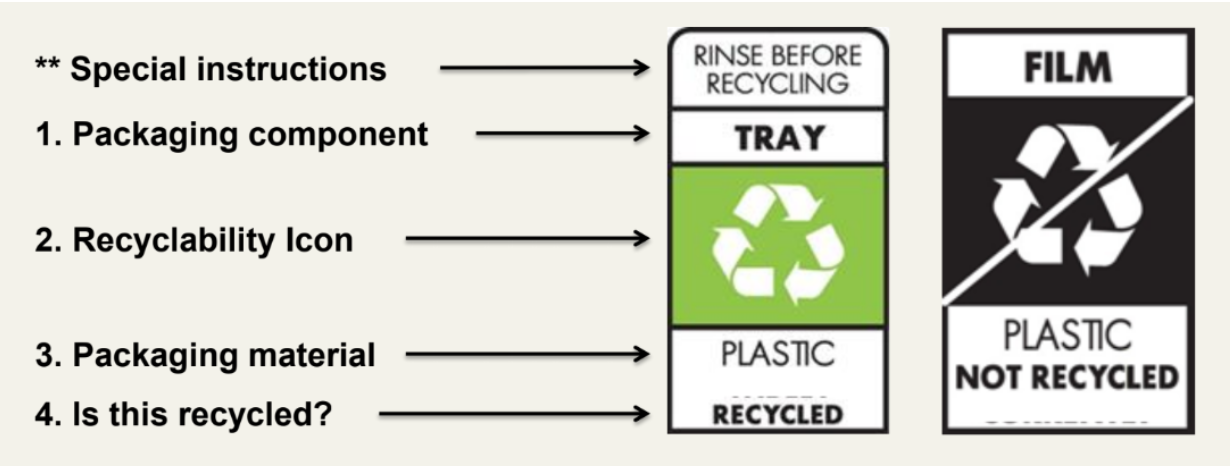

In an effort to make it easier for consumers to recycle their plastics WWF has secured commitment from six major retailers in SA to print clearer packaging labels. Currently, packaging is marked with a triangle that is made up of three arrows which surround a number that indicates what kind of material it is made of. Consumers need to look up the codes as they do not directly state whether materials can be recycled.

The new design will state clearly which packaging component it refers to, whether it’s recyclable, what the packaging material is, and whether it is already recycled.

Woolworths, Clicks, Spar, Shoprite, Checkers, Pick n Pay, and Food Lover’s Market will all soon adopt this new labelling. This effort is part of a larger initiative led by WWF and SAPRO to decrease plastic waste, known as the South African Plastics Pact.

WWF’s Project Manager Circular Plastics, Lorren de Kock, welcomes recycling efforts but says it is not the answer to the wider plastics problem.

“Ultimately, we need to stop generating more and more plastic waste and to find ways of reducing our consumption and reusing the materials that are already in the system in a meaningful way. While recycling is part of the answer, it is not a panacea for the plastic waste problem and industry and government must also get involved,” she said.

Consumers must also put pressure on producers by speaking up and refusing non-recyclable products. However, de Kock agrees that this is harder for poorer people to achieve than it is for wealthier consumers who can afford more expensive alternatives.

“It’s difficult because plastic is the cheapest material out there, and our poorer communities rely on it for packaging. You can’t tell someone in an informal settlement not to buy the cheapest product on the shelf because it’s wrapped in plastic.” she said.

Hanks believes that those with the means to act must do so and she is actively working to change the behaviours of her peers. The endurance runner, plastics activist and environmental writer is the co-driver of a national campaign to change the way water is managed during running races in South Africa. The #icarrymyown campaign is gradually gaining traction and race organisers are beginning to turn way from plastic sachets – instead providing water tanks that allow runners to refill their own containers.

“It’s a radical shift in how we move, what we drink, what we eat, everything. Interrogate everything. Be curious. Double check. Test it in your own compost heap.”

It’s time to rattle cages, she said.

“We can’t mess around anymore; we can’t keep talking about it. We’ve run out of time for meetings.”